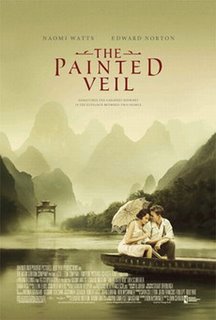

What is incalculable in human beings—thereby, summarily exempt from the feckless foibles of expectation and disappointment—becomes the cradle of what can ultimately be apprehended, respected and perhaps even loved. Or so W. Somerset Maugham suggested in his 1925 novel The Painted Veil, recently adapted for the screen by Ron Nyswaner (Philadelphia), directed by John Curran (We Don't Live Here Anymore) and starring Naomi Watts and Edward Norton, who have likewise co-produced the project.

Though Maugham's The Painted Veil has been turned into a film twice before—first in 1934 as a melodrama with Greta Garbo and then in 1957 as The Seventh Sin—this most recent adaptation is the brain child of Edward Norton, who has nurtured the project for the last six years.

Norton portrays Dr. Walter Fane, a bacteriologist who falls in love with Kitty (Naomi Watts), an upper class London socialite. Their hasty marriage is not based on reciprocal feeling. Kitty has accepted Walter's proposal primarily to escape the disapproval of her mother. It is 1925 after all and Kitty is risking becoming an old maid and a burden to her parents. Walter becomes her ticket to a new life in Shanghai, China.

Set against a backdrop of social upheaval and the breathtaking landscapes of China's Guangdong province, their unique love story evolves. Kitty, reckless and selfish, has been unfaithful to Walter, engaging in an illicit affair with Shanghai's handsome but married British vice consul, Charles Townsend (Liev Schreiber). A retaliatory Walter, hurt by his wife's indiscretion, shifts them to the remote village Mei-tan-fu under the pretext of helping out against a cholera outbreak. The decision is challenging and dangerous for both of them. Under such extreme conditions they are forced to resolve their flawed expectations.

The performances in this ensemble are provided in taut measures; mannered eloquent by way of restraint. Edward Norton—whose mirthful eye waxes expressive—manages to convey immense feeling—passionate infatuation, bitter rancor, as well as gradual reassessment. Naomi Watts shifts from a spoiled woman blinded by selfish concerns to someone whose eyes open commensurate to her heart. Their conflicted interaction set against such an exotic locale (sensuously filmed by Stuart Dryburgh) will invite easy comparisons to David Lean (Doctor Zhivago, Ryan's Daughter) and Anthony Minghella (The English Patient). It certainly is as classic—and effective—a romance as any of those.

Supporting roles are all competent. Toby Jones—released from the grip of Capote—portrays Deputy Commissioner Waddington, the Fanes' only neighbor in Mei-tan-fu. Anthony Wong Chau-Sang is statuesque as General Yu, begrudgingly setting aside differences with Walter Fane to deter the cholera epidemic. Liev Schreiber as the handsome strategist Charles Townsend forces Kitty to examine her fruitless desires.

Diana Rigg as the Mother Superior, particularly, lends so much through so little. She has always been one of my favorite actresses, ever since I was a young boy and in love with her characterization of Emma Peel in the British television series The Avengers. It's odd the moments actors provide that stay with you throughout a lifetime. When Diana Rigg left The Avengers, I recall her character descending a flight of stairs and encountering her replacement to whom she offered the key advice that John Steed (Patrick Macnee) preferred his tea stirred counterclockwise. All these years later, that has stayed with me.

The film's desultory piano accompaniment by Lang Lang accentuates the gradual awakening of unexpected grace, defined by the Mother Superior as the combination of love and duty.

Not having read W. Somerset Maugham's novel, I'm not exactly sure what he is conveying in the image of a painted veil. Does it refer to Inanna's nakedness after the seventh veil has fallen? Whether or not, the film's opening montage is a masterful superimposition of historical tableaux, bacterial activity, and floral evanescence, suggesting that beneath surface appearances, behind the incalculable, is what we must learn in order to love.

Cross-posted at Twitch, where Diana (whose LiveJournal site Fire of Spring is literate and lovely) responded to my query about Maugham's use of "the painted veil" with this educated response:

The title is meant as a reference to Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Lift not the painted veil which those who live." The sonnet goes:

Lift not the painted veil which those who live

Call Life: though unreal shapes be pictured there,

And it but mimic all we would believe

With colours idly spread,—behind, lurk Fear

And Hope, twin Destinies; who ever weave

Their shadows, o’er the chasm, sightless and drear.

I knew one who had lifted it—he sought,

For his lost heart was tender, things to love,

But found them not, alas! nor was there aught

The world contains, the which he could approve.

Through the unheeding many he did move,

A splendour among shadows, a bright blot

Upon this gloomy scene, a Spirit that strove

For truth, and like the Preacher found it not.

Cross-published at Twitch.

No comments:

Post a Comment