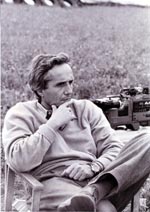

Before introducing Marco Bellocchio at the New Italian Cinema screening of Good Morning, Night, San Francisco Film Society programmer Linda Blackaby acknowledged the presence of Francesca Calvelli—editor for both Good Morning, Night and Bellocchio's latest The Wedding Director—and Sergio Pelone, the producer of both films.

In his early films like Fists in the Pocket, China Is Near, and In the Name of the Father, Blackaby outlined, Bellocchio became very well-known for dealing with contemporary social and political issues, first in Italy and then internationally. His recent films My Mother's Smile and Good Morning, Night, the 28th and 29th films in his career, returned to that earlier time of the 70s to look at their influence on the present. Blackaby brought Bellocchio to the microphone to introduce his film. Robin Treasure translated expertly and smoothly.

Humbly, Bellocchio said, "What can I tell you? Nothing. Those who have preceded me have already said many beautiful nice things and they may suffice. As you'll see [Good Morning, Night] describes a very tragic point in Italian history, the kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro. Of course I did this in a very personal way, my own way, but, I did follow the book written by Anna Laura Braghetti entitled Il prigioniero (The Prisoner). She was one of the Red Brigades, which is the group that kidnapped Aldo Moro. In this way the entire film is very internal. It takes place within this apartment where Aldo Moro was held in custody for 55 days. Unfortunately, I can't really tell you to enjoy the film because this is a tragic film; but, at the end if you do have some questions, I hope I'll be able to respond in merit."

* * *

At film's end, while the credits rolled, Bellocchio accepted questions. One fellow wanted to know how much of the film was invented? How closely had Bellocchio stuck to the actual record? Americans especially are unfamiliar with the details of the Aldo Moro kidnapping.

The film, Bellocchio responded, is based on the book that was written by a woman who was one of the Red Brigades who held Aldo Moro in captivity and killed him, which of course is in some ways represented by the character Chiara portrayed by actress Maya Sansa. This is not a historical film, however. It doesn't have a historical value. The true difference between actual history and this film is what is seen here at the end of the film. The woman who was actually a part of the Red Brigades wrote in her book that she did have some pangs of conscience, she was struggling, but in the end she went through with what the Red Brigades had set out to do, which was to assassinate Aldo Moro. Whereas in Good Morning, Night Chiara appears, at least, to have decided to go completely against their wishes and go with her own conscience to liberate Moro. Of course what you have here in the film are two parallel endings, two parallel possibilities. You have one in which it is imagined that Aldo Moro is liberated and another ending in which he is actually killed.

Bellocchio was asked what the reaction of the Moro family was to his film? Bellocchio qualified that Aldo Moro had a large family. His son Giovanni Moro really appreciated the film. Some of his daughters who saw the film have not expressed an opinion. But another daughter—the mother of the grandson that Aldo Moro adored so much—expressed opposition to the film for personal reasons.

One woman said her impression of the film was that Bellocchio sympathized with the Red Brigades by humanizing them despite their assassination of Aldo Moro and wondered if that had been his intention? Bellocchio conceded that she was entitled to her impression and her own interpretation of the film, but personally he didn't feel any affinity or bias for the Red Brigades in any way. What he wanted to highlight in his film was the deep pathology underlying the Red Brigades' ideology. They reached the utmost in a lack of humanity, which was to have no regard for another human life, to kill Aldo Moro—not because he's a human being—but because he represented something. Ironically, it's the highest point of a lack of humanity, it's as inhumane as you can be, and yet they thought they were doing the utmost in the name of humanity. But, of course, there was a lot of responsibility that lay in the hands of the political body as a whole as well. They were completely unyielding in terms of having any kind of negotiations with the Red Brigades, except for one part of the Christian Democrats and the Socialist party as well. They thought that if they gave in even just a little bit, it would result in total chaos and the destruction of the republic. But Bellocchio doesn't subscribe to that. As. J. Hoberman indicated in his Village Voice review, Bellocchio has suggested Moro "was a martyr to establishment cowardice." Bellocchio and many others would have preferred that there be negotiations. But that's not what prevailed and, since we can't repeat history, that's how it went.

Bellocchio was asked if negotiation was always the best tactic? He admitted he was not a politician and couldn't answer in general terms; but, in this particular situation, he would have favored negotiations. He is against the death penalty and doesn't believe in it in any case. That won him a round of polite applause.

As to why he wanted to make this film 25 years after the events and why he wanted to return to them to take another look, Bellocchio said that—although this was a very personal film—it had originally been proposed to him by Rai Cinemafiction, the state Italian broadcasting system, and—though he was very young at the time—he did live through it. He felt it was an important opportunity for him to reflect on an important political event.

Queried whether he would ever pursue a sequel that delved further into the political ramifications of the Aldo Moro affair, Bellocchio quickly discounted any interest in doing so. That, Bellocchio suggested, should be a task that the historians take on to examine it further, to look at the documents and study it further. There are, of course, two hypotheses: the Red Brigades say—and their version is—that everything is as they have said it was, meaning there is no alternative explanation for what happened. What they know is the truth. The other hypothesis is that it was either the CIA that was behind the assassination, or the KGB, and that it was convenient to have Aldo Moro killed. That statement agitated Bellocchio's audience and hands shot up everywhere. Some didn't await turns and cried out for explanation.

Aldo Moro, Bellocchio clarified, was the architect of what was called the Compromesso Storico, the Historic Compromise, which meant that he brought the Communists into coalition with the Christian Democrats. The CIA wasn't happy with that, of course, and hence that second hypothesis.

One woman then cheekily wanted to know the impact of this episode on Italian politics. The audience laughed incredulously. Perhaps you should read a few books, Bellocchio countered slyly. Hundreds of books have been written on just that subject. Salon's Andrew O'Hehir has recommended Leonardo Sciascia's The Moro Affair, for starters.

One gentleman reminded that Good Morning, Night was not the first time Bellocchio portrayed the Red Brigades; they had shown up in his earlier work China Is Near. That film portrayed a very young man, a Maoist, and the gentleman wanted to know how Bellocchio perceived that film's relation 40 years later to his current work. That angry young person was willing to throw a bomb into a public toilet. Bellocchio, in turn, reminded the gentleman that China Is Near was a comic film about a Maoist group perceived in a comic way. For Bellocchio, the tragic anger in Good Morning, Night is more closely connected to his first film Fists in the Pocket where the mother is killed, matricidal anger. But the big difference is that in Good Morning, Night you have this imaginary ending where Aldo Moro lives, where there's hope, where he's free. That's very different from the ending of Fists in the Pocket where it ends in complete tragedy.

The final question was a graceful segue away from political issues to aesthetic considerations of how Bellocchio edited his films and incorporated sound and music. Bellocchio said that Good Morning, Night was made by using some stock footage. The film also incorporated different usages of music. His editor Francesca Calvelli was responsible for suggesting he use Pink Floyd; music from her generation. His music—more lyrical opera—is from a previous generation. He felt that Pink Floyd's music really expressed the kind of rage and desperation that the Red Brigades were experiencing at that time. He integrated many different choices of music, stock footage and archival television coverage—which of course provided an external view—he incorporated all of that to create one single piece. He tried to make free use of that in that way.

Cross-published on Twitch.

No comments:

Post a Comment