I was grateful that the East Bay Express asked Frako Loden to write up the Pacific Film Archive's two-day program of Kihachirô Kawamoto's puppet animation. With her firsthand knowledge of Japanese culture and a scholar's eye for detail, she succinctly previews the program's fare. Along with Jasper Sharp's Midnight Eye overview of Kawamoto's oeuvre and his interview with Kawamoto, as well as Miguel Romero's notes on his sabbatical encounter with Kawamoto, I felt informed and prepared.

Admittedly, I only caught the first evening of Kawamoto's animation but it was enough to recognize his genius and to appreciate the beauty of his craft. His first piece—Breaking of Branches is Forbidden (Hana-Ori, 1968)—lightheartedly moralizes about the "pleasures and punishments" of drinking sake. A temple's head monk orders his young acolyte to guard a beautiful cherry blossom tree while he goes out. A samurai warrior and his servant arrive at the temple and want to feast under the branches of the cherry tree. At first, the acolyte refuses, but when he smells the sake, he succumbs to their generosity. He ends up passed out drunk dressed in women's clothing and responsible for the cherry tree's broken branch. "Here Czech mentor Jiri Trnka's influence on the early Kawamoto is most evident," Frako writes but distinguishes "that the characters' faces originate in traditional Japanese theatrical forms like kyogen—an origin shared with, say, Gimme Gimme Octopus of 1970s children's TV animation." (For those interested in pursuing Frako's references, the Japan Arts Council has an excellent webpage on noh and kyogen and Film Threat has reviewed the dvd of Gimme Gimme Octopus (Kure Kure Takora). Further, I've discovered a sampling of the inanity, plus an MP3 for those who can't get enough.)

Returning to Kawamoto, he claims the worst year of his life was the one spent raising money for Breaking of Branches Is Forbidden. Without a distributor, Kawamoto solicited his audience and exhibited the film in a rented hall.

I love the acolyte's face and bald head in this piece, so foolish and cavalier, whimsical. One of Miguel Romero's most interesting observations—among many—is about Kawamoto's puppet heads. He writes, "The most distinguishing feature of [Kawamoto's] puppets is the heads. Although smaller than his fist, the heads convey an amazing degree of psychological subtlety and depth. In demonstrating how he makes the heads, he revealed his secret. He covers the papier maché heads with kidskin. This gives the puppet's skin an exceptional smoothness and translucent quality. Since most of his puppets feature articulated eyes and mouths, the total effect, while not necessarily realistic, is very lifelike in its total effect."

Frako points out how Demon (Oni, 1972) evokes "the mysterious transformational power of mothers, especially on the threshold between life and death" and notes the story is a Japanese medieval legend Konjaku-monogatari from the same 12th-century anthology as Rashomon. Jasper Sharp states Demon's "plain black backdrops and minimalist design seems more explicitly inspired by the traditional theatrical forms of Noh and Kabuki theatre, and bunraku doll dramas." Demon concerns two brothers, both hunters, who live with their elderly mother. One day, the brothers go to the mountains to set traps for deer. Suddenly, from the top of a tree, a demon's arm reaches out and grabs the younger brother. The older brother shoots an arrow, severing the demon's arm. When they examine the arm the brothers make their "grisly discovery"—that the arm resembles their mother's.

With A Poet's Life (Shinjin No Shogai, 1974), Kawamoto ventured into cut-out animation (kirigami), departing from his puppets, because he didn't think "the story was well-suited to puppet animation." But he wasn't sufficiently pleased with that venture to continue cut-out animation. After A Poet's Life, he decided not to do it anymore. "Puppets make their own story," Kawamoto explained to Midnight Eye's Jasper Sharp, "while with cut out animation the story is created by the animator."

Sharp writes: "A Poet's Life is based on a story by Kobo Abe (1924-1993), a number of whose works, such as Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another were adapted for the screen by Hiroshi Teshigahara in the 1960s. Similar to Teshigahara's films, Kawamoto presents us with a fable which is as thought-provoking as it is incomprehensible, this time detailing an old woman working at a factory mass-producing clothing who one day mistakenly manages [to] fall asleep at the loom and weave herself into the fabric of a woolen jacket."

Winter has never been such a bitterly-cold snowflake as it is in A Poet's Life. I was moved by the film's ending: A mother rat scavenging to build a nest for her babies, inadvertently scratches the old woman's heart in the woolen jacket, which slowly becomes bloodstained with her death.

Kawamoto combined kirigami with his puppets for the surreal Travel (Tabi, 1973) wherein a young girl sets off on a physical journey, which is also an inner voyage through which she will learn all the pain and joy of life. The journey changes her completely but when she returns she is the only one who knows how she has changed. The poem in the film is by Su Tong-Po, a famous Chinese poet. Sharp found Travel's flat 2D collage style "reminiscent of Terry Gilliam's work for Monty Python, cross-referencing well-known works by surrealist artists such as Salvador Dali, Paul Delvaux and MC Escher in a deeply Freudian tale in which a young girl wanders lost through a cavernous museum space doubling as her subconscious."

But though conceding Travel was "beautiful, dreamlike work", Sharp had to ask Kawamoto directly what it meant. Kawamoto explained that in the Spring of 1968 the Soviet Union invaded Prague and killed a lot of Czech people. "The film is about the Life of Suffering," he said, "Buddha says that life is suffering and there are four basic sufferings: birth, disease, aging and dying. These are the four major sufferings in a person's life. There are a further four sufferings that Buddha spoke about. These are having to meet people you find annoying, being parted from a loved one, not getting the things you desire, and the sufferings of the mind and body. In order to get rid of those sufferings one must achieve a state of satori, or enlightenment. This is the theme of Travel. All of these elements of the eight sufferings are contained within that movie. The main character of the girl wonders if the Indian man she meets might be her lover from a former life. There's a scene where she drops the statue she is holding."

Whereas Sharp considers the 19-minute Dojoji Temple (1976) Kawamoto's most "traditionally inspired", Frako Loden describes it as a "harrowing" and "well-known tale of a girl who falls in love with a resistant pilgrim. Demonized by her unrequited feelings, she turns into a lethal serpent that encircles the huge temple bell he hides in and incinerates it, leaving him an ashy skeleton—another victim of earthly desire."

"Stylistically," Sharp furthers, "it resembles the yamato-e narrative picture scrolls of traditional Japanese art, with its watercolor backdrop of flattened compositions and non-converging parallels running to the horizon. With virtually nothing in the way of dialogue, it is one of the most lyrical and mesmeric of [Kawamoto's works]."

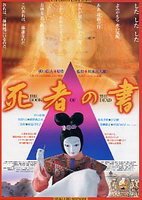

The evening's pièce de résistance, however, was The Book of the Dead [Person] (Shisha no sho, 2005), Kawamoto's second full-length feature and his magnum opus, which world premiered as part of a Special Retrospective Tribute to Kawamoto at the 40th Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, an event which likewise commemorated Kawamoto's 80th birthday. The Book of the Dead is stunningly beautiful and complex. Just to watch the fabric on Kawamoto's puppets waver in the wind is enough to make you believe in magic all over again.

Kathy Gertiz's evocative synopsis suffices: "Set during the Nara period in the mid-eighth century, when Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China, this hauntingly beautiful puppet animation intertwines two poetic stories. The first is based on a true story of a young noblewoman, Iratsume, who studies Buddhism, meticulously making copies of the amida sutra. After seeing what she believes to be a vision of the Buddha, she journeys to a temple. There she learns the story of Prince Otsu, who was executed fifty years earlier. Obsessed by a vision of a young woman, an ancestor of Iratsume, who witnessed his death, Prince Otsu's ghost haunts the temple in the belief that Iratsume is the woman of his vision. The two battle through many nights, one longing for the material world, the other striving for the spiritual. Driven to make this film because 'the world is now confused and in panic, and there is war happening for no reason,' Kawamoto expresses the Japanese Buddhist concept that the souls of those who are killed must be consoled, saying, 'I am trying to heal those innocent people who have died in recent wars.' "

Frako embroiders the theme by stating, "The elemental force of earthly desire beyond the grave is the theme that takes Kawamoto's exquisite animation beyond the fairy tale and into the realm of spiritual transformation. It seems natural that his stories come from medieval tales and Noh plays, set as they are in the enchanted spirit world of Buddhism."

For those who want a sampling of the work, Twitch provides a lovely Japanese trailer. This entry is also cross-posted on Twitch.

05/16/07 UPDATE: Dean Bowman has written an informative essay on The Book of the Dead for Midnight Eye.

No comments:

Post a Comment