First thing Saturday morning John Ford's Bucking Broadway with Harry Carey, Sr. was introduced by Joseph McBride, the author of many notable books on film history, including Searching For John Ford: A Life and Whatever Happened to Orson Welles? (due out this October).

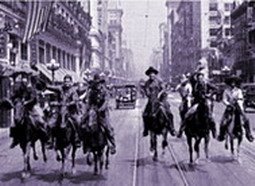

McBride expressed his delight in having Harry Carey, Jr. present as a living emissary of the John Ford stock company and as the representative of a family that spans the entire history of American films. His father Harry Carey, Sr., the star of Bucking Broadway, was originally a D.W. Griffith actor, as was his mother, the wonderful Olive Carey. Harry Carey, Sr. was a big star in the silent era and he was John Ford's mentor and tutor in the early years; Ford learned an awful lot from him. Astoundingly, Bucking Broadway was made when John Ford was only 23 years old. He made nine films in 1917—the first year he directed—and Bucking Broadway was one of them. A lot of the early Ford-Carey westerns were lost and a few of them have gradually been rediscovered over the years so, for McBride, it was a treat to see one of them intact on 35mm. The print of Bucking Broadway was accidentally discovered in a French archive six years ago where it had been misfiled. Thus, McBride considered it "a real treasure." McBride claimed that—those unfamiliar with Harry Carey, Sr.—would be astounded by how natural an actor he is, way before the modern acting style had developed. He was just very easygoing, very natural. John Wayne modeled himself after Harry Carey, Sr. and said he was the greatest of all western actors.

I wasn't wild about Bucking Broadway, was expecting more, though I could appreciate its historicity. I was bothered by its portrayal of women as weak-minded and weak-willed, and its racist portrayal of Blacks. In one scene Cheyenne Harry (Harry Carey, Sr.) wants to impress his beau Helen (Molly Malone) and shops for a new suit. He tries on a series of suits that don't fit, either the sleeves are too long, or they're too short, but, finally he settles on one. He steps outside feeling the dandy and then discovers that there's a Black man wearing an identical suit bought at the same store. I could have accepted the broad humor of this had it been another cowboy wearing the same suit but for it to be a Black man indicated to me that it was so far beneath Cheyenne Harry to wear what a Black man would wear, such an insult, that he had to go back into the store and throw the suit in the proprieter's face.

After the screening of Bucking Broadway Harry Carey, Jr. joined Joseph McBride on stage. Carey had difficulty maneuvering the stairs and required assistance. When he finally sat down, he quipped, "That was about the worst entrance I've ever made." His humility immediately endeared him to his audience.

Highly recommending Harry Carey, Jr.'s book, Company of Heroes, McBride stated the chapter on Three Godfathers was so "hysterically funny" that he almost fell on the floor laughing. Further, he stated it was the best account of John Ford at work, and a clear, complex and intimate portrait suffused with deep understanding. McBride pointed out that Harry Carey, Jr. had been in nine John Ford films, including some of his greatest (such as The Searchers).

Harry Carey, Jr. conceded he had been in three really great westerns. "I guess I was just very very lucky," he said humbly. One was a non-Ford—Howard Hawks' Red River—and then She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and The Searchers. Three "pretty good" westerns.

It was strange for him to see his dad so young in Bucking Broadway. The film had been made in 1917, four years before his birth. For him it was amazing how much his grandson Alec resembles his dad. "He's a great looking guy, wasn't he?" Harry Carey said proudly of his father, initiating a round of applause.

Harry Carey, Sr. and John Ford were a great team. According to his mom—who was a great bright tough lady—the young John Ford and his father—who was about 18 or 19 years older than Ford—had a real fine relationship but, because of gossip between other actors, his dad and Jack Ford parted ways. The break wasn't that serious as far as friendship went; they still saw each other three or four times a year even after they stopped making movies together. Perhaps they could have gone on making even more films together but they made 20-some. Irritated, Harry Carey, Jr. claimed it was "so typical of Universal" not to take care of those Ford-Carey films, letting them rot away in a vault somewhere. Of the 26 movies that John Ford and Harry Carey, Sr. made together, only about 3-4 of the features and parts of several others have survived.

"What's amazing to me," McBride asserted, "is that it's a small fraction of what they made together but they're all completely different in terms of their storyline, their tone, they're not formula pictures at all even though they have genre elements, and they're very low-budget. I love the unpretentious quality of these films, they're just very easygoing and relaxed. You see Ford's great eye for composition in the very beginning of his career with those beautiful long shots and the depth of compositions, don't you?"

"Yeah, that's marvelous," Harry Carey, Jr. agreed, pointing out that Ford also loved his "action stuff." Watching the fight scene at the end of Bucking Broadway reminded Harry Carey, Jr. that Ford used to just let his actors go during those fight sequences. He didn't want to routine it, or block it out or rehearse it. He would say, "Fight" and that was it. Frequently on set you would walk up to somebody and they'd have a bloody nose or cut eye. Carey broke three ribs in one film and suspects it was Jack Ford who broke them while providing instructions. The way Ford staged his fights was to encourage a big free-for-all.

Ford was 21 years old when he directed Bucking Broadway which Carey considered a "terrific movie and a terrific western." He used to sit at the breakfast table with his father and a man named Joe Harris, who was in a lot of the old pictures. Joe ended up staying with the Careys at their ranch for years and years as a kind of foreman and gave up motion pictures. Harris was Harry Carey, Sr.'s closest friend. Over breakfast Harry Carey, Jr. would hear their stories about John Ford and the making of those westerns in the silent days. "I grew up listening to those stories so it's always a pleasure to see one of them."

"What did your father say about John Ford? What kind of memories did he have?" McBride asked. Harry Carey, Jr. responded that he would "start at the end and then go backwards." Because about a year before his father passed away, about 1946, Carey, Jr. said, "Pop, how come you don't work for Jack Ford anymore?" He thought his father would say, "Oh, I don't want to go through all that again and blah blah" but he didn't. He just said, "He won't ask me." That's all he said, "He won't ask me." He paused for a minute and then he predicted, "…but you will." He qualified, "Not til I croak"—that was the expression he used—"After I croak, you will." Of course, the day after his father passed away, Jack Ford cast him in Three Godfathers. "He knew him pretty good," Carey, Jr. praised his father and admitted, "If I had told that story to John Ford I would never have worked for him again." Three Godfathers begins with an affectionate dedication to Harry Carey, Sr: "To Harry Carey—Bright Star of the Early Western Sky."

Ford kept telling Carey, Jr. before they started shooting Three Godfathers, "You're going to hate me when the picture's over; but you're going to give a good performance." He kept saying, "You're going to hate me when the movie's over but you're going to give a good performance." "I didn't hate him after the film was over," Carey, Jr. emphasized, "I hated him after the first day! [Laughter.] It was a horrible experience! [More laughter.] If it wasn't for Duke—John Wayne—I would have gone home. I said, 'He doesn't like what I'm doing. I'm going to go home.' Duke said, 'No, he loves what you're doing.' To which Carey, Jr. responded, 'Well, how can he act like that and like what I'm doing?' And Duke insisted, 'He's doing it for a reason.' " Three Godfathers was his roughest role and, even though he went on to make nine or ten more films with Ford after that, Three Godfathers was his roughest, toughest experience.

McBride mentioned that his current favorite Ford film is Wagonmaster, a "perfect movie" in which Carey, Jr. had a part. "It's like those early films with your dad, it's very low budget, it's just a bunch of friends out in the beautiful wide open spaces." McBride wanted to know if Wagonmaster was a fun film to shoot?

"It was the most fun of all!" Carey, Jr. affirmed. Working for Jack Ford was like a vacation. Wagonmaster was the first film in Moab, Utah, a tiny town since grown big. They'd never had a movie location there. Wagonmaster was the first one. It only cost Ford about a half a million dollars to make the pic (which even for those days was a cheap-budget). But it was a charming little picture and one of John Ford's favorites, something he said all the time. In fact, he said it was his favorite a few times. But Ford made so many great films that it's hard to pick one out that is really better than any other. Wagonmaster had the distinction, however, of being the most fun Carey, Jr. had on a Ford set.

At this juncture McBride noted that Harry Carey, Jr. was called "Dobe" by his friends because his father named him that the day he was born. "Dobe" explained: "I had this bright red hair when I was born and my dad thought it was like that red adobe clay that was there on the ranch and we lay around in a house built out of adobe. He'd never say it was an adobe house, he'd say, 'It's a 'dobe house.' So he nicknamed me Dobe and I've been Dobe ever since. I thought about using Dobe as my regular motion picture name and people have always thought that it was Warner Brothers Studios that made me use Harry, Jr., but, actually it was my dad. When I got a part at Warner Brothers, the first part I had was in a picture called Pursuit with a very young Robert Mitchum. Dobe was 25 and Mitchum 27 or 28. He asked his dad whether to use Dobe or Harry, Jr. for his stage name and his father said, "I'd like you to use Harry, Jr. and carry on the name." Since that was his father's request, that's what he did, though his Mom was resentful of the choice. She wanted him to use the name Dobe. "Too bad, Mom," he apologized, "that's the way it is." Whenever John Ford introduced Dobe, he always referred to him as Harry Carey, Jr.

John Ford was present when Dobe was born. Ford and Dobe's father were getting drunk that day, May 16, 1921. "The same birthday as Henry Fonda and the same birthday as Liberace," Dobe stated to much laughter. "Yeah, that's quite a combo." Increased laughter.

From the audience Jim Kitses, author of Western History: Horizons West, asked if John Wayne was consciously emulating Harry Carey, Sr.'s gesture of holding his left bicep with his right hand at the end of The Searchers. It was a gesture that his dad did a lot in real life. He would stand and talk like that with his one arm crossed over his chest. "Duke was shooting the tag of The Searchers," Dobe answered, "and he looked to camera left or right—I can't remember which—and he saw my mother was right in his eyeline and that's what made him do that. He just went like that as a tribute to my dad. Every time I see that it really knocks me for a loop. It's a beautiful moment."

McBride quoted Ford as saying that Harry Carey, Sr. was a thinking actor and that you could see clear into his soul. His characteristic gesture was pensive.

"John Wayne was a terrific actor to work with," Dobe recalled. "When you're doing a scene with him, he'd give it everything. You could play off of him so well because he's a very honest actor and a very sincere actor, no phoniness, or making faces or stuff like that for Duke Wayne. He was always great doing scenes with. I remember—I think one of the last shows I did with John Wayne was called Big Jake and I played an older—I was only in my 40s at the time and I played an old man, a mean old guy with brown teeth and great big beard. I thought that he would object to my playing that role. And he [didn't], he was very supportive and it was something that I enjoyed doing very much. I was like 43-44 and played a guy in my 60s. So all the way to the end he was great to work with, all the way to the end."

McBride clarified that as Dobe became middle-aged, Ford continued casting him as a young guy. Yeah, Dobe smiled, "I'm 85 and I think he'd have me playing a guy 20 years old." He was always a kid to Jack Ford. One of the last great visits between John Ford and his father was out at John Ford home—a beautiful estate he bought for the guys in his outfit. There were 18 of the boys in his outfit who were killed in action and so it was a shrine to all of their memory. He dragged his father out there to go horseback riding and Ford showed up. He and his father sat beneath a tree and talked continuously for four hours, catching up on each other's lives. "It was wonderful to see," Dobe recalled, "It was not too long before my father passed away."

Harry Carey, Jr. was asked what the working relationship between John Wayne and Montgomery Clift was like in Red River?

"Not so hot," Carey, Jr. responded. Apparently, Wayne wasn't too fond of Monty Clift. Of course, Carey, Jr. didn't know that when he was working on Red River. Partly because he only worked on the film for three weeks and was only in a couple of scenes, though one really good scene with Wayne. "I would have been on that show for twelve weeks had I been cast in the beginning of it," he explained, "But what happened was we were up in a place called Elgin, Arizona, right outside of Tuscon, they were shooting there and the young man who was playing the part of Dan Latimer said that he was sick and couldn't work on this particular day so Hawks said, 'Well, send him to the doctor and we'll shoot something else.' That night when Hawks was in the town of Tuscon, he saw this young actor in there partying and having a good time and realized that he wasn't sick at all so he fired him. Evidently, the story was that he mentioned to Duke Wayne, 'I don't know who to get to play this part of Dan Latimer. I fired this kid and I can't think of a young actor to do it.' And Wayne said, 'Well, I don't know if he can act or not but Dobe Carey looks a lot like the part' and Hawks said, 'That's a great idea!' So I should have given him 10% of my salary; he got me a part."

Montgomery Clift and John Wayne didn't have a lot in common even though Clift made a tremendous hit in Red River because he brought a style to the screen that had never been seen before. "A lot of people attribute Marlon Brando for bringing that style of acting and actually it was Monty Clift that first did that mumble stuff. I admire Monty Clift. I admire Marlon Brando a great deal. I admire both of them. He and Wayne were not too compatible. They were just great on the screen."

Peter Nellhaus continues his coverage of the 2006 SFSFF at Coffee, Coffee & More Coffee, including his take on Bucking Broadway.

No comments:

Post a Comment