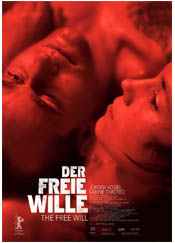

As is often the case, it was Dave Hudson's report from the 2006 Berlinale to The Greencine Daily that alerted me to Matthias Glasner's Der Freie Wille / The Free Will. The film walloped him hard at an early morning screening and has been running neck to neck with Requiem as his favorite film of 2006. The Berlinale's prestigious Silver Bear for artistic contribution to cinema was presented to Jürgen Vogel for co-writing, producing and starring in The Free Will and he picked up another award at the Chicago International Film Festival. It is, unquestionably, his courageous performance as Theo Stoer, a convicted rapist struggling to rehabilitate, that—as Variety's Derek Elley states it—sustains this "tough verismo love story." Vogel's performance is matched beat for beat by Sabine Timoteo as Nettie Engelbrecht, an abused young woman who becomes romantically entangled with Theo. Their mutual woundedness—one might say their mutual indebtedness—delivers the hardhitting and nearly unbearable pathos of The Free Will.

At first the film's title seems a deliberately disturbing misnomer. Charlie Prince meditated on this when the film had its North American premiere at Tribeca. "It's unclear to me," he wrote at Cinema Strikes Back, "if the title of the film The Free Will is meant to be an open question or a sarcastic contradiction of what is presented on screen." Worrying the conundrum, Prince argues that—given the film's title—one has to ask whether Theo has "free will" to control what he calls "the beast" within him and stop committing such heinous acts? "[I]t is hard to believe the director intends to condemn the character for committing these horrible crimes of his own free will," Prince conjectures, "to me it seemed like he was portrayed as up against a force within him that was beyond his control, a potentially controversial assertion."

Prince's concerns are philosophically apt and it is to the filmmakers' credit that these concerns are poised for consideration. The Free Will honors its audience's intelligence and sophistication as few films on this subject do. Leaning on Wikipedia's guidelines, the general definition argued by some theists regarding the role of free will in relation to the existence of evil is that God allows evil to exist so that humans can have freedom of choice, to do good or evil, so that they are whole beings, and not mindless machines. In other words, the general premise is that good and evil are products of free will. Thus, there can be no good nor evil without free will. Concomitantly, to remove evil would be to remove free will, which would also remove all good or—as the song fears—"If I exorcise my devils; my angels may go too." To remove all evil becomes a hazardous proposition because it likewise removes all good; a hazard that one might even categorize as evil. Consequently, free will becomes necessary as a divine manifestation of God. Or so the argument spins around and around while one munches the maligned apple.

Variously, one could argue that free will is—if not impossible then at least partial—and that the choices a person makes are determined by one's inherent nature. In the case of Theo it meant he willed himself to be good, he "wanted" to be, he "tried", but that doesn't necessarily mean he "gets" to be good. And this is perhaps what is most disturbing about our sympathy for Theo and Nettie; it's really more an empathy with their struggle to do the right thing when the right thing might not be who they are or what destiny has in store for either of them. Clearly it doesn't. We all can relate to that a little bit, I think. In this respect, Theo's conflict is much like Henry's in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer or Ripley's in The Talented Mr. Ripley where our sustained engagement with their plight becomes something of a morbid fascination with the inevitable. We wish against the inevitable. We try with choice even as we succumb to the fateful twists of individual tragedy.

Theo's anguished efforts to tame the sexual violence within him is rendered poignant by the world's commodified resistance to his best intentions. In other words, we're taught not to be violent, even as the world—indeed the universe—rages ubiquitously around us. Or worse, seethes underneath seemingly normal and complicit interactions, as David Lynch is fond of glamorizing. We're taught to control sexual impulses even as we are bombarded with sex as a commodity. Sex sells everything, Joni Mitchell sings, and sex kills. Theo is desperately struggling to stifle impulses within him that are tempted out by everyday life: by sexy underwear ads in deserted subway stations that assert—larger than life—fascist representations of desire. He tries to ignore young women even as they seem perpetually around him, alone, challenging his beast with their unsuspecting vulnerability.

This is why The Free Will is a challenging piece of filmmaking. It strips complacency away layer by layer to expose bare fears. Another concern it poses is that—as author Lawrence Durrell states it—understanding does not constitute a cure. No amount of rehabilitation or therapy can disguise basic instinct when it is as raw and driven as Theo's or—for that matter—Nettie's. When Theo kept saying, "I can't do this. I can't do this", my heart leapt into my throat, out of pity, out of fear, out of disgust, out of anger. Once again the basic dilemma is presented as a failure of will which is perhaps not as free as continually suggested. The scenario feels rigged.

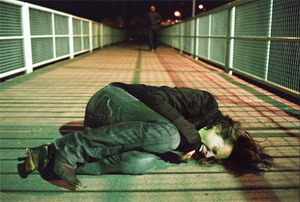

Yet another of the film's provocations is its dalliance with the uncomfortable premise that there is an inarticulate dynamic that attracts abusers and their victims to each other to work out their fates through each other. This belies a complicity that denies the horror of random violence. Not that we accept random violence but we can digest it more readily. We can somehow accept it as a fact of

life. But we remain horrified by the gravitational dictates of fate that draw individuals willingly into harm's way. Somehow the fact that Theo does not rape Nettie, that he tries so hard to have a normal relationship, is fundamentally more abusive to her than, let's say, the rape of Alex in Gasper Noé's Irreversible, a film to which The Free Will is often compared. Alex's rape is a spectacle of cosmic determinism. The abuse that Nettie suffers is more profound because that determinism has been resisted. Again, they both try, they both want, and they both don't get.

The tension of this dynamic is rendered in one of the film's most revealing scenes where Theo and Nettie "meet cute" in their own way, she not liking guys and he not liking girls, and so they take it to the martial arts mat to work it out. Their mock punches progress into articulated honest aggressions and defenses.

As powerful and important a film as I think The Free Will is, I wouldn't be able to call it one of my year's favorites. I'm ambivalent about its length but moreso about a certain staged conflict Theo endures when he breaks into and enters the apartment of a potential victim. The scene rang completely false for me and pulled me out of what—until then—had been a prolonged grandeur. That Theo was able to break into her apartment without waking her up or her hearing him or anyone noticing him just seemed completely out of character with the way his violence had been demonstrated beforehand. I even found myself chuckling over the notion that, perhaps, German women are just really sound sleepers and don't notice when stalkers break into their apartments, remove their covers and slip into bed beside them. Perhaps I'm just an envious insomniac. But that's really just a minor bitch in a film that is searing for its refusal to endorse any easy exits. In the end the film suggests that our only true free will is to remove ourselves from the arena of choice. A slice of life bitter for human veins to accept.

Cross-published at Twitch.

No comments:

Post a Comment