To celebrate the centenary of Little Nemo, the boy dreamer whose fantastic adventures in Slumberland are chronicled in Winsor McCay's dazzling early-twentieth-century comic strip series, John Canemaker delivered a special presentation at Pacific Film Archives based on his critically acclaimed, newly expanded biography

Winsor McCay: His Life and Art. The lecture was illustrated with stunning images from the book, as well as 35mm archival prints (courtesy of

La Cinémathèque québécoise) of four of McCay's greatest films:

Little Nemo (1911, 3 mins), the first adaptation of a comic strip to a film format; the indelibly disturbing

How a Mosquito Operates (1912, 6 mins);

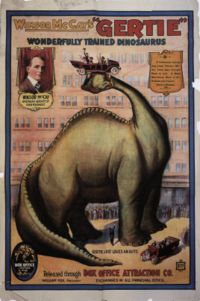

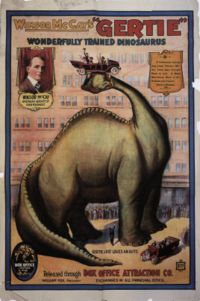

Gertie the Dinosaur (1914, 18 mins), the charming and infinitely influential animation McCay designed as part of a Vaudeville act; and

The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918, 12 mins), a somber animated counterpart to McCay's editorial cartoons. All four films were accompanied on piano by Judith Rosenberg.

This was a magnificent evening of cinematic education and bewonderment (a word I've had to invent to describe my feelings). I could literally feel my eyelids widening in amazement, trying to soak in as much as possible of what I was being shown and being taught about

Winsor McCay by animation historian

John Canemaker. Cinematic experiences such as these are far and few between. I've transcribed Canemaker's introduction and some of his commentary during the projection of the McCay animations to provide my readers a sample of this unique and memorable evening.

* * *

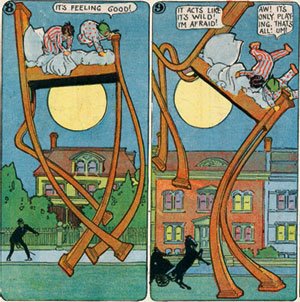

Once upon a time, a little over 100 years ago, on Sunday, October 15, 1905 to be exact, a pleasant surprise awaited readers of

The New York Herald newspaper. Among their favorite color comic strips was a new offering from the prolific Winsor McCay. On the last page, a full newspaper page, this is what they saw [Canemaker projected the first installment in the

Little Nemo series].

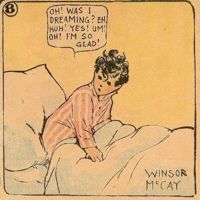

Little Nemo in Slumberland was unlike any comic strip before or since. For its creator the cartoonist Winsor McCay had represented a major creative leap far grander in scope, imagination, color, design and motion experimentation than any previous comic strip that he or his peers had ever attempted. For readers,

Little Nemo in Slumberland became an exhilarating weekly fantasy adventure, a cartoon epic, a sustained drama both visually beautiful with a compelling cast of developing personalities, chief among them the boy dreamer Nemo. By the way, the model for Nemo—a juvenile everyman whose name is Latin for "no one"—was someone very important to Winsor McCay: his nine-year-old son Robert. [Canemaker projected a photograph of McCay with his son Robert in their Brooklyn house, up on the second floor where McCay created his wonderful comic strips].

Each week, McCay would slowly reveal Slumberland bit by bit as it gradually became clearer to him. This dream-like unraveling of the story was how Lewis Carroll discovered Wonderland and how L. Frank Baum led us to magical Oz: two classical works of fantasy of which

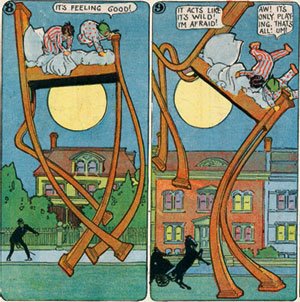

Little Nemo is the creative equal. Week after week, readers were enthralled by an extraordinary array of ravishing imagery that stays in the mind like remembered dreams. McCay's virtuoso draftsmanship is irresistible when butterflies seek shelter from the rain under an umbrella tree, or the open mouth of a giant dragon becomes the traveling coach, or a walking talking icicle escorts us up the cold staircase of Jack Frost's palace, or a walking bed—who likes to get out once in a while—goes for a jaunt down the streets and across the roofs of 1908 New York City.

Within a year of its debut,

Little Nemo was translated into seven foreign languages and

Victor Herbert composed music for a lavish operetta adaptation of the script that opened in the fall of 1908 on Broadway at the New Amsterdam Theater, the current home of Disney's

The Lion King. Speaking of merchandising, the popularity of the strip led to numerous consumer products such as articles of clothing, sheet music, playing cards and other games.

Little Nemo in Slumberland, a child's version of the mythic theme of the quest set in a dreamworld, is quite simply the most beautiful and innovative comic strip ever drawn. It is ultimate eye candy. McCay's style combined a sensuous art nouveau line with subtle yet daring coloring. Architectural perspectives are stunningly rendered and sequential changes of characters and settings within the borders of the strip's flexible panels showcase the artist's natural gift for animation.

In his talent for vividly capturing motion in drawings, McCay may have been gifted similarly to Leonardo daVinci. Sir Kenneth Clark once described the extraordinary quickness of Leonardo's eye: "There is no doubt that the nerves of his eye and his brain were really supernormal and, in consequence, he was able to draw and describe the movements of a bird, which were not seen again until the invention of the slow motion camera." The same could be said of Winsor McCay.

Inevitably, McCay turned his artistic focus toward film animation and, once again, his work represents a quantum leap in the direction of that nascent art form. McCay distinguished his animation from his contemporaries by the sophistication of his drawing style, the application of narrative continuity, the fluid movement of characters, and his attempts to inject personality traits into those characters. He introduced a film version of

Little Nemo into his vaudeville act. Yes, McCay was also a stage performer. He was a vaudeville headliner since he first "trod the boards" in 1906 and in his act he drew quick, "lightning sketches", as they were called, on a blackboard to a musical accompaniment and, yes, he

did play the Palace.

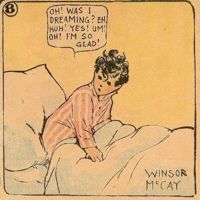

McCay's first attempt at animation [was] based on his

Little Nemo comic strip. Alone, he drew the nearly 4000 sequential drawings and the film played in movie theaters starting April 8, 1911. McCay also used it in his vaudeville act including a live action prologue at New York's Columbia Theater, which was located at 62nd Street and Broadway (it's no longer there). Audiences at the time were amazed by the lifelike animation. A contemporary reviewer said: "One is almost ready to believe that he has been transported to Dreamland along with Nemo and is sharing his remarkable adventures and it is an admirable piece of work that should be popular everywhere."

Four years after McCay's death in 1934,

Claude Bragdon wrote: "I shall never forget McCay's first animated picture. In pure line on a white background a plant grows up and a young man plucks it and hands it to the girl beside him. That's all there was to it but it excited me greatly and no wonder; I had witnessed the birth of a new art."

Little Nemo

"As you are about to see," Canemaker prepared us, "there was a great deal more to this brief film." He commented on

Little Nemo over Judith Rosenberg's inspired piano accompaniment.

Little Nemo begins with a live action prologue where Winsor McCay, identified by Canemaker as seated on the right, initiates a bet among his friends that he can make his drawings come to life. Said friends include

John Bunny, the large man next to him who was one of the earliest screen comedians. McCay is then shown at his drafting board and the audience is provided a rare glimpse of how he drew his work. "He had the extraordinary ability to work with very little construction lines underneath," Canemaker advised. "He was actually able to start at the top of the drawing and work down and have it completed by the time he got to the bottom. When he made posters and billboards in the Midwest, he did the same thing. He would stand on a box—he was a rather diminutive man—and crowds would gather to watch this amazing thing happen in which figures would be drawn from the top of the image straight down to the bottom.

Damon Runyon wrote about seeing McCay in the Midwest do this."

The main characters from the

Little Nemo strip are introduced as McCay's hand on the screen draws them. On the left is the Imp, in the middle is Nemo himself in his full Slumberland regalia, and on the right is the bad boy, his nemesis, Flip.

"McCay wanted to make sure that you knew that

he had drawn these characters, that

he actually created them. This photographing of the hand of the artist is one the oldest visual motifs in animation. You've often seen it in many cartoons, including Chuck Jones'

Duck Amok in which Daffy Duck is driven crazy by Bugs Bunny drawing him. Here he is making a big deal about bringing these drawings to life. [His friends] think he's crazy. Again he has to convince them—and you—that he is the god-like creator of these characters." Watching McCay draw his characters also emphasized that they were not

yet moving so that when they "come to life" with very fluid movement—which Disney emulated some 20 years later—the effect is quite stunning.

Though the film states the animations were completed a month after the bet, Canemaker cautions that is, of course, not accurate. It took much longer because McCay was a very busy man. "He was doing his vaudeville act, he was creating these elaborate comic strips—not just

Little Nemo but

Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend and several other strips, including advertisements. So it took him much longer than one month to do this. Now, again, to emphasize how difficult this task is going to be, he staged this scene where barrels of ink and tons of paper have got to be pushed into his studio."

Canemaker describes McCay as "a very natty dresser" who was "always dressed up in a vest and custom made shirts with cuffs. He always wore his hat when he worked and smoked his little cigars; cheroots he called them."

McCay is then shown surrounded by tall stacks of original art from the film. On his desk we're shown a device, which reveals "how he pencil tested his work before there were pencil tests, which animators use to see if the animation is working smoothly. It's based on the old things from the nickelodeons where you go into see a photograph moving, or cartoons. This is not his house. This is a set. It was filmed at the

Vitagraph Studios on Avenue M in Brooklyn. The Vitagraph Studios

still exist. In fact,

The Bill Cosby Show was shot there for many years recently."

The film then provides a close-up look at the original drawings. "They were made originally on very delicate rice paper and they were attached by glue in six places on cardboards that had registration crosses in the corners so that McCay could register them so they wouldn't shift all over the place. He would make crosses on the rice paper as well. The rice paper allowed him to see through several sheets of paper at the same time. At that time there were no peg holes or peg bars that they could attach the drawings to over a light table. That came a couple of years after this."

This demonstration in the film "was characteristic of McCay in real life. He didn't mind telling everyone how he created animation. He loved the art form very much. He wanted to get the information across to people so when people would ask him questions or come back[stage] after his vaudeville act, he would tell them how it was done." Further, the film shows how the film drawings were held and how McCay hand-painted each frame.

Canemaker alerted our attention to "the wonderful, fantastic perspective animation of the dragon as he moves out of frame. Amazing. McCay always contrasted the fantastic with the mundane." The film ends and Canemaker comments, "Yay, Mr. McCay!" He then returned to his presentation.

Winsor McCay's Biography

Let me tell you a little bit about Winsor McCay. Winsor McCay was born in 1867 in Canada and raised in Michigan. He was basically a self-taught artist who learned his craft through experiences on the open road and the exigencies of commercial deadlines. In Chicago, in 1889 at age 22, he was employed by a printing company that made circus posters. Two years later he moved to Cincinnati to work as a poster painter for the local dime museum, which was a popular combination of freak show, vaudeville and curio museum. In Cincinnati in 1891, he met and married Maude DuFour and the couple had two children: Robert and Mariam.

By 1898, McCay was an illustrator on the

Cincinnati Commercial Tribune newspaper and he was a contributor of gag cartoons to national humor magazines such as

Life. In 1900, he joined the

Cincinnati Enquirer where three years later he created his first proto-comic page,

Tales of the Jungle Imps, which ran from January to November, 1903. By November of 1903, however, he and his family were living in New York City. McCay had been hired by the

New York Herald newspaper. [Canemaker then showed us a photo of bustling

Herald Square, which was known as the Tenderloin at that time around 34th Street. He advised that Herald Square was named for the small, elegant Italianate Herald Building right in the photograph's center, designed by

McKim, Mead and White.]

Fame quickly followed McCay due to the popularity of his numerous comic strips, including

Little Sammy Sneeze, a boy whose violent nasal explosions wreak havoc resulting in punishment by rejection in the last panel, even though the subtitle said he never knew when it was coming. There's a wonderful one in which he destroys his own panel. Another strip starred

Hungry Henrietta, a little girl with a voracious appetite, who adults ply with food instead of the love she really needs and wants. [Canemaker then showed us an example of "a disastrous meeting between Sammy Sneeze and Hungry Henrietta" wherein Henrietta, due to Sammy's not knowing when a sneeze is coming, ends up with food all over her face.]

Another strip—one of the greatest and most sophisticated and wittiest comic strips ever for adults is

The Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. Each week a man or a woman experiences an intense and often horrific nightmare usually in a mundane setting. In the final panel the disturbing dream is blamed not on drugs or alcohol but on innocent Welsh rarebit, which is a concoction of melted cheese cooked in cream and ale and served on toast. Yuck. These are wonderful nightmarish trips. [Canemaker then showed us an example of the strip "seen from the point of view of the deceased. Here's the dead person looking up at what people are saying, and they're saying terrible things. The wife is saying, 'Why did you leave me without a cent?' The priest is saying, 'He's no good. He was never any good.' A terrible nightmare."]

Then in 1905 came McCay's masterpiece

Little Nemo in Slumberland. But, for the artist himself, he said it was his work in animated films that would always remain "the part of my life for which I am proudest." We will now screen both the second and the third of McCay's animated films—

How A Mosquito Operates from 1912, which was based on a

Rarebit-themed comic strip, this one, from 1912, and one of the most famous of the silent-era animated films ever made,

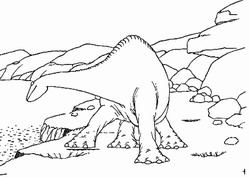

Gertie the Dinosaur from 1914, which was also preceded by this comic strip version. Both films demonstrate McCay's growing interest in telling stories creating characters with distinctive personalities. McCay's tiny mosquito and gigantic dinosaur reveal personality traits that reveal their thought processes, and thinking cartoon characters, in turn, produce actions that affect audiences' emotions.

[Canemaker showed us some of the original drawings from

Gertie the Dinosaur.] Again, seeing these up close you can see that there is a delicate rice paper on which the characters are drawn and then that is placed over cardboard with printed x's that the animator McCay would trace over and that would hold the drawing in place for him. The backgrounds were done by a young man who lived in the neighborhood named John Fitzsimmons, he was 18 years old, and I had the privilege of meeting him and doing a documentary film about him. But he had the nervewracking job to retrace that background that you see there on every drawing, on all the hundreds of drawings that McCay did, McCay did the character; Fitzsimmons did the background.

Like Walt Disney years later, McCay wanted to convince you that his cartoons were real and he did so through precise representational draftsmanship, smooth naturalistic motion and believable timings and effects. His visual sophistication [was] 20 years ahead of Walt Disney.

Gertie the Dinosaur, in fact, was the film that inspired numerous artists who later joined the Disney Studios.

Gertie the Dinosaur

The date is wrong. It's 1914 when this film was made and exhibited. Again, there's a prologue. Again, it's McCay betting his friends—including

George McManus, the creator of

Maggie and Jiggs—that he can make an animated film on a prehistoric animal come to life. [Canemaker replicated what McCay would do in his vaudeville act and requested assistance from his audience to achieve McCay's earlier interactivity. Apparently, McCay would come out on stage and crack a whip and the projectionist would project Gertie on the screen and then McCay would make her behave.]

[In the scene where Gertie picks up a rock and flings it at Jumbo the mastodon, Canemaker commented, "I want to point out to you that in great animation the feeling of weight to that rock, having to drop it once and pick it up again adds a great believability. For animators to put weight into their characters is really quite extraordinary." Canemaker explained that McCay timed himself breathing in and out in order to get this sequence right where the dinosaur is breathing in and out. In the scene where Gertie drinks up the water in the lake, Canemaker once again drew our attention to how the ground gives way beneath her, another indication of believable weight. Canemaker then explained that McCay by this time would have walked offstage right, returning onscreen as the cartoon version of himself where he takes a ride on the back of Gertie.]

The Sinking of the Lusitania

The Sinking of the Lusitania, the evening's final offering, was McCay's fourth film of the ten films that he made. "This one took him nearly three years to make with the help of two assistants, one was John Fitzsimmons and the other was a man named Aptford "Apt" Adams, who was a buddy of his from Cincinnnati. It is McCay's first production using cels—celluloid acetate—a money and timesaving technique in which the characters were inked and painted on transparent celluloid and placed over opaque painted backgrounds. Released in 1918,

The Sinking of the Lusitania is a monumental work in the history of animation. While it did not revolutionize comic cartoons of its time, it is a milestone that demonstrates the possibilities that the medium offers to creative animation filmmakers. The film's dark, somber mood, the superb draftsmanship, the timing of the animation, the dramatic directorial choices for camera angles and editing: all these qualities would reappear years later in Disney's mature work in his feature-length cartoons and in WWII propaganda shorts. The ship Lusitania itself, sailing serenely in the beginning, and then attacked and reeling from a fatal wound, and finally in an achingly slow death throe, suggests an amazing sentience and an emotionalism without overt or crude anthropomorphism.

"The incident was the 9/11 of its time. There's an eerie correspondence between the World Trade Center attack and the sinking of this ship and its unexpectedness on a placid day, and the imagery of falling bodies, smoke and fire and the helplessness of the victims.

The Sinking of the Lusitania was widely admired but McCay's magnificent achievement could inspire only awe from his peers. It was way ahead of its time in 1918 in content and technique and far beyond the sensibilities and capabilities of contemporary animators churning out simple gags in films starring clowns, kids, dogs and cats."

[

The Sinking of the Lusitania starts out with McCay conversing with a Mr. Beech who was a reporter for the Hearst papers. "There were no photographs taken of the disaster but Mr. Beech was the first reporter in Europe to get the details from the survivors. So he was telling McCay what he needed to know." Canemaker likewise draws notice to "a certain framing device around the image that's moving. Again, they still didn't have peg holes and peg bars so Fitzsimmons suggested that they cut out a book, cut out the center of a book cover and put it over the cels to hold them down, which is why you see this frame throughout."

The Sinking of the Lusitania was a sad, beautiful piece. Its animation resembled lithographs. I was impressed with how Edith Rosenberg, who had never seen the film before, was able to play her piano straight to the dark heart of the piece.

* * *

So that was Canemaker's presentation on Winsor McCay. I hope my transcription has helped you take part in an event you may not have had the fortune to attend.

Thom at

Film of the Year has provided a link to a creative

French bio-fiction of Winsor McCay, which includes beautiful samplings of

Little Nemo and a French rendition of

Petite Sammy Éternue, which animates his sneeze via Flash Micromedia!